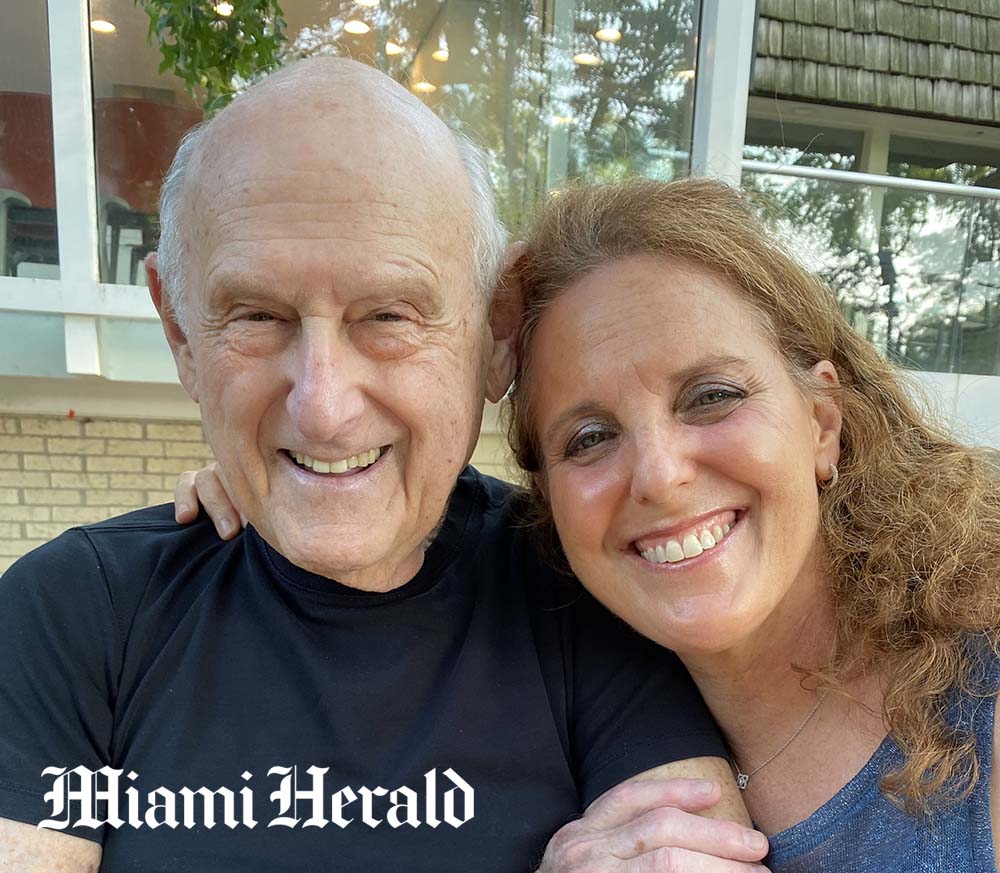

As I head to the gym, I’m struck with the urge to call my father. I’m 55 years old and he’s 90, but still, I need for him to know.

“What’s up?” he asks.

“Going to the gym,” I say, fake-offhandedly.

“And?”

“Forty minutes of cardio intervals, 40 on weights.”

Pause. “Good, but not sufficient,” he says, kidding, but not.

Growing up, weight and exercise were at the forefront of our relationship. “Exercise is like a magic pill you take,” my father would say, his bony index finger jabbing the air. “Every single day.”

I believed him. I agreed! But no amount of self-loathing and shame — and I generated plenty of both — could force me into line.

He was like a Marine in Afghanistan, except that he was a lawyer in Prairie Village, Kansas. Running every day, he’d pound his body into the pavement, then plunge each leg up to his groin into a wastebasket of ice. There he’d sit, ripping through the pages of the latest New Yorker, freezing his traumatized legs for exactly 30 minutes. Who could compete?

Not me. I’d pull on my too-tight red track shorts (better to gasp for air than buy a bigger size) and huff around our block, simmering with a mix of self-loathing and resentment. Then I’d give up.

So much seemed to depend on my ability to exercise — my character, my thinness, my future marriage prospects. And my failure reflected the worst sin of all: sloth, a moral failing second only to gluttony, of which I was also guilty.

I hung onto the family edict like a rope, swinging between yes and no, pride and shame, all the while cursing my own diseased psyche.

Like legions of my contemporaries, I spent my 20s and 30s slogging through step classes, Nutrisystem, Jenny Craig, aerobics, the Zone Diet, hot yoga, the South Beach Diet, on and on. None of it stuck.

By my mid-40s, I finally found my way around my twin adversaries of weight and exercise. (Even managed a great marriage prospect and two great kids!)

These days, I mostly play master. “Hey Dad, looks like you’ve gained a few pounds,” I’ll say, patting his belly. We play, we joke, we take our roles. He scolds, I scold back.

Our routine keeps our attention off the new, painful beast between us: his failing body. After a lifetime of beating himself into submission, he’s mostly bone on bone. Both shoulders are held together by failing tendons, both hips by metal and ceramic.

Last time I was in Kansas City for Thanksgiving, the physical therapist came for him. “You need to practice your walking, Jack!” she shouted in a too loud, too singsongy voice. I saw my father shake his head.

Old age is rife with indignities, but it has wondrous gifts. My father has softened. Time has cleared away the brush and noise to reveal in all his relationships what has always flowed beneath. Love and constancy. His devotion and deep desire for what all fathers want: for their children to be happy.

Today, I see my father whole. I relish the complex, loving person he is and the depth and richness of our relationship. I see how his love was never about talking, but doing — in always finding time, taking interest, constantly loving and giving without expectation of thanks.

I pray my father will be around for many more Father’s Days, so he can keep giving our kids unsolicited critiques, telling them to cut their hair, stand up straighter, go here but not there for college. But time has melted these exchanges into blessings. He’s still doing the best he can — just as we are with our own children.

One day too soon, I’ll drive to the gym, and there will be no one to call. No one who cares about my exercise regime, no one to ask why I need butter on my bread. And of course, I’ll miss that more than I can possibly imagine now.

Call it Stockholm syndrome, but I suspect millions of daughters and sons are out there with me pining for that gold star from their father, no matter how old they are or how crazy it is.

They say love is stronger than death. They say that love is eternal. All I can say is, it better be. Because when the day comes that my father’s no longer here to judge my workouts or nod at my finally fit physique, I’ll be counting on his starry love to carry me through.

This article was originally published in The Miami Herald.